- Home

- Elizabeth Peters

Borrower of the Night vbm-1 Page 21

Borrower of the Night vbm-1 Read online

Page 21

‘At first, everything seemed to be working out for the lovers. Burckhardt practically handed the shrine over to them by sending it to Rothenburg in Nicolas’ charge. Nicolas murdered or bribed the guards and brought the shrine to the Schloss alone. He and Konstanze hid it in the tomb of the old count. Then Konstanze wrote that letter to her husband saying that the expedition had never arrived.’

‘He kept her letters,’ Tony muttered. ‘Carried them around with him, brought them here . . .’

‘He was a stupid sentimentalist,’ said Blankenhagen, looking contemptuously at Tony. ‘Stupid not to suspect such a story . . .’

‘We didn’t suspect it,’ I said wryly. ‘And he was deeply in love with her; love has a very dulling effect on the brain. There was no reason why anyone should have been suspicious. Even when we found Nicolas’ body, and the wing that had been broken off the shrine, there was no evidence to show that Konstanze knew anything about it.

‘After that night, when Nicolas appeared as the Black Man, he went into hiding. He couldn’t be seen hanging about; Konstanze meant to kill her husband, if he wasn’t killed in battle, but until he was dead she couldn’t let him get suspicious. And he wasn’t the only one who had to be deceived. The bishop was after the shrine and he was giving Konstanze a hard time. I’ll bet her reputation was already shaky. The mere fact that she read authors like Albertus Magnus and Trithemius would be enough to start nasty gossip.

‘So Burckhardt came home from the wars, hale and hearty, and delighted to see his loving wife. She didn’t waste any time. He was taken ill the day after his return.

‘On the crucial night, the night of the steward’s murder, the conspirators decided to move the shrine. We’ll never know why; Burckhardt was dying, so maybe they thought it was safe to proceed with their plans. At any rate, there they were, down in the crypt; I can see Konstanze holding the lamp and Nicolas working on the tombstone. He raised it. The shrine was lifted out, losing a wing in the process. And then . . .

‘Then they looked up and saw, in the lamplight, the face of the man they had robbed and cheated and tried to murder. God knows what aroused him, or how he got the strength to come looking for them. But he was there. He must have been there. He saw the lovers, with the shrine between them, and he knew the truth. You can’t blame him for turning berserk. The theft of the shrine was bad enough, but the knowledge that his servant and his beloved wife had cuckolded him . . . he went mad. By the time he finished Nicolas, who must have put up a fight, Konstanze was gone – with the shrine. I suppose she had someone with her, a servant maybe, who had helped with the heavy work. She could quietly bump him off at any time with her handy store of arsenic. Nobody asked questions in those days about the death of a serf.

‘After stabbing Nicolas and throwing him down at Harald’s feet, like a dead dog, Burckhardt piously closed his father’s tomb. What I can’t get out of my mind is a suspicion that Nicolas wasn’t dead when the stone was lowered. If you remember the position of the body . . . Well, enough of that. It certainly wouldn’t have worried Burckhardt. Having disposed of one traitor, he went after his wife. He would have killed her too, if it hadn’t been for the nurse, who thought he was delirious. She testified to his insane strength and mentioned that his dagger was not at his belt. But Burckhardt was half dead from arsenic poisoning. They wrestled him back into bed, and Konstanze finished him off in the next cup of gruel.

‘Maybe he had time, before he died, to whisper an accusation to a servant or priest. Maybe not; she would have watched him closely, and arsenic doesn’t leave a man particularly coherent. In any case, the bishop got suspicious. He disliked Konstanze anyhow. So she got her just deserts, by an ironic miscarriage of justice – though I think the punishment was worse than the crime.’

‘Death by arsenic poisoning is exceedingly painful,’ said Blankenhagen.

‘I know. But the count had helped torture Riemenschneider and had bashed in the skulls of a lot of miserable peasants who were only trying to get their rights . . . I guess they were all rotten.’

‘So we figured,’ Tony said sweepingly, ‘that the shrine had to be in the countess’s room. The count had the whole castle at his disposal, but she was limited to her own room.’

‘We,’ I said. ‘Yes.’

‘One more thing,’ Tony said, ignoring me. ‘I don’t think anyone else caught this. Remember Irma’s cry at the séance – das Feuer? That was the result of Schmidt’s hypnotic talents and the Gräfins gruesome stories; but what I didn’t think of until later was that Konstanze didn’t know German. She was a Spaniard, and she and Burckhardt probably communicated by means of the Latin spoken by the noble classes in those days. So if she had given a last frantic scream, as she may well have done, it would have been in Latin or Spanish. In other words – no ghost.’

‘Obviously,’ I said.

‘Sooo clever,’ murmured Irma.

‘That’s about it,’ I said briskly. ‘No more questions?’

‘Only my heart’s gratitude,’ said Irma mistily. ‘Now I go to see that we have a celebration dinner. I cook it with my own hands, and we dine together, yes? And a bottle of Sekt.’

‘Sekt,’ I said glumly. Sekt is German champagne. It is terrible stuff.

Irma departed, to cook her way into somebody’s heart. I wondered whose heart she was aiming for.

I looked from one man to the other. Neither of them moved.

‘Well,’ I said.

‘I want to talk to you,’ said Tony to me, glaring at Blankenhagen.

‘And so do I,’ said the doctor, staying put.

‘Go ahead,’ I said.

‘If we could have some privacy . . .’ said Tony, still glaring.

‘I do not mind speaking in your presence,’ said Blankenhagen. ‘I have nothing to hide.’

Tony said several things, all of them rude. Blankenhagen continued to sit.

‘Oh, hell,’ said Tony. ‘Why should I care? All right, Vicky, the game is over. It wasn’t as much fun as we expected, but it had its moments. So – speaking quite impartially, and without bias – who won?’

‘Me,’ I said. ‘Oh, all right, Tony, I’m kidding. Speaking quite impartially, I’d say we came out about even. It was partly a matter of luck. You would have fingered George sooner or later – if he hadn’t fingered us first. I solved the murder of Burckhardt, but primarily because I was the one who found the arsenic. Shall we call it a tie?’

‘That’s all I ever wanted to prove,’ said Tony smugly.

‘You’re a damned liar,’ I said, stung to the quick. ‘You were trying to prove your superiority to me. And you did not. I didn’t need you at all. I could have figured out the whole thing – ’

‘Oh, you cheating little crook,’ said Tony. ‘You said you would marry me if I could prove you weren’t my intellectual superior. I proved it. I didn’t need you, either. I could have handled this business much better if you hadn’t been around getting in my way and falling over your own feet – ’

‘Liar, liar,’ I yelled. ‘I never said any such thing! And even if I did, you haven’t – ’ I stopped. My mouth dropped open. ‘I thought you wanted to marry Irma,’ I said in a small voice.

‘Irma is a nice girl,’ said Tony. ‘And I admit there were moments when the thought of a soft, docile, female-type woman was attractive. But now she’s rich . . . Let Blankenhagen marry Irma.’

‘No, thank you,’ said Blankenhagen, who had been an interested spectator. He looked severely at Tony. ‘You use the wrong tactics, my friend. You do not know this woman. You do not know how to handle any woman. Under her competence, her intelligence, this woman wishes to be mastered. It requires an extraordinary man to do this, I admit. But – ’

‘Really?’ said Tony. ‘You think if I – ’

‘Not you,’ said Blankenhagen. ‘I. I will marry this woman. She needs me to master her.’

‘You!’ Tony leaped out of his chair. ‘So help me, if you weren’t crippled, I’d – ’

>

‘You,’ said Blankenhagen, sneering, ‘and who else?’

‘You can’t marry her.’ Tony added, unforgivably, ‘You’re shorter than she is.’

‘What does that matter?’

‘Right,’ I said, interested. ‘That’s irrelevant. I can always go around barefoot.’

‘Shut up,’ said Tony to me. To Blankenhagen he said, ‘She doesn’t know you. You could be a crook. You could be a bigamist!’

‘But I am not.’

‘How do I know you’re not?’

‘My life is open to all.’ Blankenhagen had kept his composure which put him one up on Tony. Turning a dispassionate eye on me, he remarked, ‘You are somewhat concerned, after all. Perhaps we should hear your views.’

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘I don’t feel that I ought to interfere . . .’

‘Well,’ Tony said grudgingly. ‘I guess you are entitled to an opinion.’

He was flushed and bright-eyed, and he looked awfully cute with his hair tumbling down over the romantic bandages on his undamaged brow. In the heat of argument, or for other reasons, he had risen to his feet. Blankenhagen calmly remained seated, but he was right about his height. That was unimportant.

If it didn’t bother him, why should it bother me?

I sighed. Turning to Tony, I said, ‘Have you had a chance to read the answers to your cables yet?’

‘My God, how can you ask at a time like – ’

‘Do you know who Schmidt really is?’

Tony sat down with a thud.

‘You’re going to marry Schmidt?’

‘Schmidt,’ I said, ‘is the top historian at the National museum. I had a long talk with him this afternoon.’

‘Anton Zachariah Schmidt?’ Tony gasped. ‘That Schmidt?’

‘That Schmidt. One of the foremost historians in the world. At the moment he is a sad and sorry Schmidt . . .’

‘He should be,’ said Blankenhagen, unimpressed. ‘Such disgraceful behaviour for a grown man and a scholar.’

‘He’s a nut,’ I said. ‘What’s wrong with that? Why, the nuts found the New World and discovered the walls of windy Troy! Where would we be without the nuts? Schmidt has dabbled in parlour magic and spiritualism since he was a kid. He’s in good company. Businessmen and politicians consult astrologers; many scientists have been suckers for spiritualism. When he got on the trail of the shrine, Schmidt went a little haywire. It was his dream come true – sneaking around the halls of an ancient castle, finding a treasure, and presenting it to his precious museum. When Tony and I arrived, he had horrible visions of rich Americans stealing his prize – it had become “his” by then.’

‘Even so,’ said Blankenhagen coldly. ‘Even so . . .’

‘You’re a fine one to talk. You’re a secret nut yourself. If you were as sensible as you think you are, when I came around in the middle of the night babbling of arsenic you’d have sent me away and gone back to bed. You would have gone for the police when the knife missed Tony, instead of chasing George into the tunnel.’

‘Umph,’ said Blankenhagen, turning red.

‘Schmidt didn’t mean any harm,’ I said. ‘He’s a sweet little man. I always liked him.’

Blankenhagen’s face got even redder.

‘You are going to marry Schmidt!’

‘I’m not going to marry anybody,’ I said. ‘I’m going to take the job Herr Schmidt has offered me, at the Museum, and write a book about Riemenschneider, and also a best-selling historical novel based on the Drachenstein story. Maybe I’ll call it “The Drachenstein Story.” The plot has everything – murder, witchcraft, blood, adultery . . . I’ll make a fortune. Of course I’ll publish it under a pseudonym so the scholarly reputation I intend to build in the next five years won’t be impaired. Then – ’

‘You aren’t going to marry anyone?’ Tony asked, having found his voice at last.

‘Why do I have to marry anyone?’ I asked reasonably. ‘It’s only in simple-minded novels that the heroine has to get married. I’m not even the heroine. You told me that once. Irma is the heroine. Go marry her.’

‘I don’t want to,’ Tony said sulkily.

‘Then don’t. But stop hassling me.’ I smiled impartially at both of them. ‘You’re very sweet,’ I said kindly. ‘The trouble is, neither of you has the faintest idea of how to handle women – not women like me, anyhow. But you’re both young, and fairly bright; you can learn . . . Who knows, I might decide to get married some day. I’ll be around; if, in the meantime, you feel like – ’

Blankenhagen’s expression changed ominously, and I said, with dignity.

‘If you feel like taking a girl out now and then, I am open to persuasion.’

I smiled guilessly at him.

After a long moment he smiled back.

‘Also,’ he said coolly. ‘I will be here. I will continue to be here. I do not give up easily.’

There was a knock at the door, followed by the voice of one of the maids telling us dinner was ready. I started for the door.

Tony got there ahead of me.

‘It wouldn’t help Schmidt’s reputation if this affair were made public,’ he said meditatively. ‘I don’t suppose you intimated – ’

‘Why, Tony,’ I said, with virtuous indignation. ‘That would be blackmail! Would I resort to such a low trick?’

‘Of course not. Schmidt offered you a job because of your brilliance. I’m brilliant too,’ said Tony. ‘I imagine Herr Schmidt could find another job at the Museum, if I asked him nicely . . .’

Blankenhagen stood up.

‘You talk to me of rascals!’ he exclaimed. ‘You are an unprincipled dishonest – ’

I left the two of them jostling each other in the doorway and went humming down the corridor. The next five years were going to be fun.

If you enjoyed Borrower of the Night why not join Vicky Bliss on her next adventure in . . .

Street of the Five Moons

by Elizabeth Peters

The strange case of the jewel of Charlemagne

What does it all mean? The note with the hieroglyphs was found in the pocket of a man lying dead in an alley. The man also possessed a small piece of jewellery, a reproduction of the Charlemagne talisman. The reproduction is so exquisite that expert art historian Vicky Bliss thought she was being shown the real thing . . .

Vicky doesn’t know what to make of it all yet. She packs her bags for the sun-drenched streets and moonlit courtyards of Rome determined to find the answers, even if it kills her. But that dangerously exciting Englishman might just get in her way before she gets the answers she wants.

£6.99 paperback

Coming soon in Robinson paperback

Silhouette in Scarlet

by Elizabeth Peters

Is Vicky to be cast adrift or will love save the day?

One red rose, a one-way ticket to Stockholm and a cryptic message in Latin intrigue Vicky Bliss – just as they were meant to. Vicky recognizes the handiwork of her former lover, jewel thief John Smythe. She takes the bait, eagerly following Smythe’s lead in the hope of finding a lost treasure.

The trail begins with a priceless fifth-century chalice, which will place Vicky at the mercy of a gang of ruthless criminals who have their eyes on an even more valuable prize. The hunt threatens to turn deadly on a remote island, where a captive Vicky must dig deep at an excavation into the distant past…

Published August 2007

£6.99 paperback

Coming soon in Robinson paperback

Trojan Gold

by Elizabeth Peters

A traditional fairy tale Christmas? Or is it a mask for murder?

They say a picture is worth a thousand words but the photograph Vicky Bliss has just received gives rise to a thousand questions instead. The blood-stained envelope is all the proof she needs that something is horribly wrong.

The photograph itself is very familiar: a woman dressed in the gold of Troy. Yet this isn’t the famous photograph

of Frau Schliemann – this photograph is contemporary. And the gold, as Vicky and her fellow academics know, disappeared at the end of the Second World War.

Vicky and her fellow experts gather to renew the search and enjoy a festive Bavarian Christmas together. Their efforts are soon marred by a determined killer in their midst . . .

Published August 2007

£6.99 paperback

FB2 document info

Document ID: 2f3486db-a45c-4ab9-95e1-7545c13500ac

Document version: 1

Document creation date: 17.12.2012

Created using: calibre 0.9.9, FictionBook Editor Release 2.6.6 software

Document authors :

Elizabeth Peters

About

This file was generated by Lord KiRon's FB2EPUB converter version 1.1.5.0.

(This book might contain copyrighted material, author of the converter bears no responsibility for it's usage)

Этот файл создан при помощи конвертера FB2EPUB версии 1.1.5.0 написанного Lord KiRon.

(Эта книга может содержать материал который защищен авторским правом, автор конвертера не несет ответственности за его использование)

http://www.fb2epub.net

https://code.google.com/p/fb2epub/

Mystery Stories

Mystery Stories A River in the Sky

A River in the Sky He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12

He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12 Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6

Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6 Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3

Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3 Night Train to Memphis vbm-5

Night Train to Memphis vbm-5 Borrower of the Night vbm-1

Borrower of the Night vbm-1 The Golden One

The Golden One Trojan Gold vbm-4

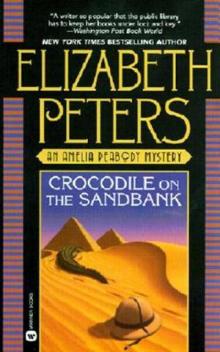

Trojan Gold vbm-4 Crocodile On The Sandbank

Crocodile On The Sandbank