- Home

- Elizabeth Peters

The Golden One Page 25

The Golden One Read online

Page 25

Ramses caught my eye, nodded, and went trotting after him. The rest of us followed more slowly. Bertie was determined to accompany us, so I walked with him, giving him little suggestions as to where to place his feet.

The shafts – tombs, I should say – were not in the main cemetery on the western hill, but on the northern slope, closer to the temple, so we did not have far to go. We found Emerson on his hands and knees – one hand and both knees, that is – peering down into a dark opening while Ramses directed his torch into it. It did not look much like a tomb entrance; the edges were broken and irregular.

“Are you sure this is it?” I inquired. “It doesn’t look like a tomb entrance.”

“Of course I’m sure” was the querulous reply. A chunk of rock broke off from under his hand. “Curse it,” said Emerson, recovering his balance without difficulty. “The whole place is falling in. Nobody has been down there for a while.”

“Which one of the princesses’ tombs is it?” Cyrus asked eagerly.

Emerson got to his feet. “None, as a matter of fact. This is the tomb where they found the reused sarcophagus of Ankhnesneferibre. Another sarcophagus was found nearby.”

“Here,” said Ramses, a little distance away.

We must have looked somewhat absurd clustered round that hole in the ground peering intently at nothing. There was nothing to be seen, not even rubble. The shaft was fairly clear, but so deep, the light of our torches did not reach the bottom.

“Nobody has been down there either,” Ramses said. “Not since – 1885, wasn’t it, that the sarcophagus was removed?”

Emerson grunted agreement. “I cannot imagine what prompted this performance, Vandergelt,” he said severely. “You might have done yourself an injury.”

“Idle curiosity,” said Cyrus with a sheepish grin.

“The view is worth the climb,” Bertie said, shading his eyes with his hand.

We were about halfway up the sloping ground that ended at the base of a precipitous cliff. It dropped abruptly to the level; opposite lay another high range of hills, and in the cleft between them we could see the Theban plain, misty green in the morning light, stretching down toward the distant sparkle of the river.

“Quite beautiful,” I agreed. “Now that we have seen it, shall we go? Nefret is expecting us for luncheon, and I want to call on Yusuf sometime today.”

We retraced our steps, down the hill toward the temple. Emerson, who had disdained assistance from Ramses, allowed me to take his arm, under the impression that he was assisting me. “Are you planning to question Yusuf?” he inquired. “I suppose we ought to.”

“I will interrogate him, yes – subtly and indirectly – but my primary motive is to be of help to the poor old fellow. I ought to have gone before.”

“Hmph,” said Emerson. It was an expression of doubt or derision, but I did not know whether he was being sarcastic about my motives or my ability to carry out a subtle interrogation. I did not ask.

“I will come with you to see Yusuf,” Selim announced.

“I would rather you did not, Selim. In fact,” I added, inspecting my escort, “I don’t want any of you to come with me. Goodness gracious, the five of you looming over him would frighten the poor old man into a fit.”

“I guess you don’t need Bertie and me,” Cyrus conceded. “We may as well go home and get spiffed up for the party.”

“Nefret will not expect you to dress, Cyrus,” I assured him. “Emerson won’t bother.”

“Selim will,” said Cyrus, directing a grin at the young man. “Can’t let him outshine the rest of us.”

Selim remained grave. “I will only do what is right. The Father of Curses does what is right in his eyes.”

“Well said.” Cyrus gave him a friendly slap on the back. “Don’t let Amelia go by herself, Emerson. Lord only knows what she might get up to.”

“What nonsense!” I exclaimed. “I am only going to examine Yusuf and prescribe -”

“My house is not far from Yusuf’s,” Selim said. “We will sit in the courtyard, Ramses and the Father of Curses and I, and keep watch.”

However, Yusuf was not at home. That elderly harridan his wife informed me that he had gone to the mosque. She did not know when he would be back.

“He cannot be as feeble as I feared, then,” I remarked. “He is able to be up and about?”

“Yes.” No thanks to you, her hostile stare added.

“Give him this.” I extracted a bottle from my medical bag. It was a harmless concoction of sugar water with a few herbs added to give it piquancy. Such placebos can be as effective as medicine in certain cases, if the sufferer believes in them. “He is not to take it all at once,” I added. “This much…” I measured with my fingers on the bottle. “Morning and night. I will come round tomorrow or the next day to see how he is getting on.”

Her wrinkled face softened a trifle. “Thank you, Sitt Hakim. I will do as you say.”

My reception by Selim’s wives was much more enthusiastic. They were both young and pretty and I must confess – though I do not approve of polygamy – that they seemed to get on more like affectionate sisters than rivals. Selim was an indulgent husband, who had become a convert to certain Western ways; with his encouragement, both had attended school. They offered me a seat and brought tea and coffee, with which they had already supplied Ramses and Emerson.

“You may as well have something,” said my son, who was sitting on a bench pretending he had been there the whole time. (In fact, he had been watching Yusuf’s house; I had caught a glimpse of him ducking back into concealment as I approached.) “Selim will be a while; he is changing into proper attire for the luncheon.”

“You weren’t long,” said Emerson. “Wasn’t Yusuf there?”

“He was at the mosque. At least, so I was told.”

“He spends too much time in prayer for a man with nothing on his conscience,” said my cynical spouse.

Selim finally emerged looking very handsome in a striped silk vest and cream-colored robe, and we bade the ladies farewell with thanks for their hospitality.

Nefret met us at the door of her house. I thought she looked a trifle fussed, and expected to hear of some minor domestic disaster. Then the cause of the disaster appeared and flung herself at Ramses.

“I couldn’t refuse her,” Nefret whispered. “She wanted so badly to come.”

“It is very difficult to refuse Sennia when she is in one of her moods,” I said resignedly as Sennia, beaming and beruffled from neck to hem, hugged Emerson and Selim. “I presume this means Horus and the Great Cat of Re are also lunching with us?”

“Not actually at the table,” Nefret said, dimpling. “At least I hope not.”

“And where is Gargery?”

Nefret gestured helplessly. “In the kitchen with Fatima. He insisted on arranging the whole affair and he has been bullying everyone, including me! Shall I ask him to sit down with us?”

“He won’t. He is very firm about keeping us in our place. He will listen to every word we say, though.”

The arrival of the Vandergelts interrupted the conversation. Everyone went on into the drawing room; but Nefret drew me aside long enough to say in a low voice, “I looked in my wardrobe this morning, Mother. Several things are missing.”

“Ah. I thought as much. I will deal with the matter, my dear. Just leave it to me.”

“I always do, Mother.”

The Great Cat of Re, now approximately the size of a melon, had to be removed from Ramses claw by claw before we could proceed to the dining room. I had not seen the room since the furniture was delivered, and some of the others had not seen it at all. The effect was extremely attractive – fine old rugs on the floor, a few antique chests, and the table itself, spread with one of the woven cloths Nefret had purchased in Luxor and with the Spode dinnerware that had been a wedding present from Cyrus and Katherine.

Amid exclamations of admiration we seated ourselves, and Gargery, in full buttling at

tire, poured the wine. I might have expected he would jump at the chance to appear at a formal meal; he considered Emerson and me very remiss in carrying out our social duties. He then stood back, stiffly alert, while the two young Egyptian girls served the food.

Most people would have been unnerved by his critical stare, not to mention the lecture he had undoubtedly delivered beforehand. Ghazela, the sturdy fourteen-year-old, was unaffected, except for occasional fits of giggles, but Najia crept about like a ghost, letting Ghazela do most of the work. The birthmark was not nearly so prominent. Nefret must have given her some cosmetic that helped to conceal it.

It is almost impossible to keep conversation at a meaningless social level with our lot, and the interesting events of the previous day were fresh in everyone’s mind. I knew Sennia would introduce the subject if Gargery did not find some means of doing so.

The child had coolly taken a chair next to Emerson and was cutting up his food for him, over his feeble protests. “Tell me again how you hurt your arm,” she demanded. “You made me go to bed last night before I heard the whole story and it is very important that I know all the facts.”

“And why is that?” I inquired, amused at her precise speech.

“So that I can help you, of course.”

Gargery coughed. His coughs are very expressive. This one indicated emphatic agreement.

Emerson glanced at me. I shrugged. Keeping the matter secret was now impossible.

“Well, you see…” he began.

Gargery had not heard the entire story either. In his interest he so forgot himself as to edge closer and closer to the table, until he was hovering over Emerson like a vulture. Emerson turned with a scowl. “Gargery, may I beg you to fill the glasses? If it isn’t too much trouble.”

“Not at all, sir,” said Gargery, backing off. “I must say, sir and madam, that I can find no fault in your actions.”

“Good of you to say so,” said Emerson, snatching the bottle from him. Gargery snatched it back.

“It might have occurred to you, perhaps,” he continued, splashing wine into the glasses, “to drop odds and ends along the way, to mark your trail.”

“Like the poor children in the fairy tale,” Sennia added approvingly.

“We hadn’t any odds and ends,” I explained, recognizing the start of one of those digressions that can, in our family, go on interminably. “Anyhow, it is over and done with. Thanks to the quick wits of Daoud, and Jumana’s excellent memory, we were found in time.”

Sennia demanded a detailed account of that, too, which Nefret gave. Jumana had spoken very little all morning and she did not add to the story, but Sennia’s praise of her cleverness brought a smile to her solemn face. “I should have remembered before,” she said modestly. “It was what Daoud said that made me think of it.”

“Memory,” I remarked, “is capricious and aberrant. It is not surprising that the import of Jamil’s remarks should have escaped you until a dire emergency recalled them to your mind. Without your assistance we might have perished in the trap he set for us.”

I had kept a close if casual eye on Najia, who had become increasingly clumsy and uncomfortable. When she slipped out of the room, observed only by me, I immediately rose.

“Nefret, will you come with me? The rest of you stay here. That includes you, Gargery.”

She had gone straight through the kitchen and out into the courtyard, and was, when I caught sight of her, trying to open the back gate. The unfortunate creature was already in a frightful state of nerves; her shaking hands could not work the latch. When I called to her to stop, she crumpled to the ground, her hands over her face, her body shaking with sobs.

We lifted her up and half carried her to a bench, and then Nefret waved me to stand back.

“She’s afraid of you, Mother.”

“Afraid of me? Good Gad, why?”

“Let me talk to her.” Her gentle voice and reassurances finally succeeded in calming the girl. She raised a face sticky with tears.

“I meant no harm. He told me I was beautiful -”

I was trying my best not to appear threatening, but the sight of me set her off again.

“I know you meant no harm, Najia,” Nefret said. “The Sitt Hakim knows that too. What was the harm in writing a message to his sister, and in borrowing my clothes? What else did you give him?”

She had not much to give, and she had given that, gladly and humbly. He had told her that he loved her, that the disfigurement did not mar her beauty in his eyes. She had never thought to attract any man, much less one as young and handsome. When he asked the loan of a few of Nefret’s clothes, to play a joke on one of his friends, she had seen nothing wrong. Not until she heard how he had used that disguise did she realize she had been an unwitting accomplice to attempted murder.

Another pitiful tale of man’s perfidy! I determined on the spot that she should not suffer for it. Seating myself next to her on the bench, I spoke quietly and firmly.

“No one else knows of this, Najia, and no one will ever learn the truth from us. Wipe your eyes…” I gave her my handkerchief. “And go home. We will tell the others you were taken ill.”

“But when my shame is known…” She faltered. “… no man will ever want me. My father will -”

“He will do nothing and no one will know unless you are fool enough to confess.” Distress had weakened her wits, which had never been very strong; I gave over trying to get her to see sense, and asserted the full force of a stronger will. “Say nothing to anyone. That is an order from me, the Sitt Hakim. We will take care of you – and find you a husband, if that is what you want. You know we can do what we promise.”

“Yes – yes, it is true.” She threw herself at Nefret’s feet. “How can you forgive me? You were so kind, and I betrayed you.”

“For pity’s sake, stop crying,” I said impatiently. My handkerchief was stained, not only with tears but with some brownish substance; the birthmark, wiped clean, stood out strong as ever. “Run along and remember that the word of the Sitt Hakim is stronger than another man’s oath.”

“That’s ‘the word of the Father of Curses,’ isn’t it?” Nefret remarked, as the girl scampered off, still swabbing at her face. “I don’t see how we can keep all of it secret, though. Someone is bound to suspect it was my clothing Jamil wore. They’d have been a tight fit, but not as tight as Jumana’s. Especially the boots. I hope they pinched horribly.”

“He probably cut the toes out or slit the heels,” I said absently. “Some people must be told some part of the truth, but it is the girl’s dishonor, as men call it, that we must hide. We may have to buy a husband for her,” I added in disgust. “That seems to be all she cares about.”

“She and a good many other women of all nationalities,” said Nefret. “Do you think she knows more than she told us?”

“Jamil is too wily to give away useful information. He even lied to his sister. What worries me,” I continued, as we strolled slowly back toward the kitchen, “is how many others he may have seduced from their duty – literally and figuratively. I fear, Nefret, that the wretched boy has caused a rift in his family that may never be mended.”

Emerson took a brighter view. I told him the whole sad story later, when we were alone, knowing his chivalrous heart would respond sympathetically to the girl’s plight. After cursing Jamil with admirable eloquence, he calmed down and said, “We’ve eliminated two of the boy’s allies. How many more can he have?”

“Some of the younger men, perhaps. There are a few who would see nothing wrong in a spot of tomb robbing. And he seems to have a way with women.”

“He selected a victim who would be particularly susceptible to flattery,” said Emerson with a curl of his lips. “Grrr! As for the men, yesterday’s events must end any influence he might have had with them. None of the Gurnawis would dare become involved with a murderous attack on us.”

“That is probably true,” I agreed.

“There’s another

angle we haven’t considered fully,” Emerson went on. “He had made himself very comfortable. I cannot see our lad abandoning his cozy little den unless he had another hiding place prepared.”

“That is also true, and no help whatever,” I said.

“I thought you were the one who insists we must look on the bright side, Peabody. We are whittling away his assets, one by one, and his repeated failures to damage us will lead him, sooner or later, into a false move.”

“Such as trying to murder us again?”

Emerson let out a shout of laughter and threw his arm round me. “Precisely. It is time for tea. Let us go down. Are the children joining us?”

“If you mean Nefret and Ramses, the answer is no. I suggested they might like to have tea alone for a change.”

“Why should they?” Emerson asked in surprise.

“Really, Emerson, you of all people should not have to ask that question.”

“Oh,” said Emerson.

“Jumana and Sennia will be with us. That should be entertainment enough for you.”

They were on the veranda, sitting side by side and looking very pleased with themselves.

“Only see what Jumana has given me,” Sennia shouted.

“Unless the Museum takes it,” Jumana warned.

“Yes, you said that, but I know Mr. Quibell will let me have it, he is a very kind man.”

It was the little stela with the two cats which I had seen Bertie copying. I admired it all over again, while Emerson smiled sentimentally at the two. Sennia had not been an admirer of Jumana’s, perhaps because she was aware of Jumana’s admiration of Ramses. I gave Jumana credit for wanting to win Sennia’s friendship. A present is a sure way of influencing a young child in one’s favor.

Fatima brought the tea and Emerson settled down with his pipe, and I began looking through the post. There was a several days’ accumulation of letters and messages, which I sorted, putting aside the ones directed to Nefret or Ramses, and opening the envelopes addressed to Emerson before I handed them to him.

Mystery Stories

Mystery Stories A River in the Sky

A River in the Sky He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12

He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12 Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6

Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6 Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3

Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3 Night Train to Memphis vbm-5

Night Train to Memphis vbm-5 Borrower of the Night vbm-1

Borrower of the Night vbm-1 The Golden One

The Golden One Trojan Gold vbm-4

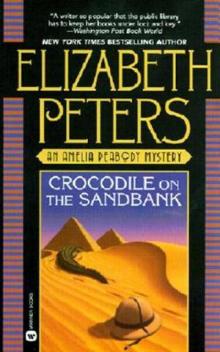

Trojan Gold vbm-4 Crocodile On The Sandbank

Crocodile On The Sandbank