- Home

- Elizabeth Peters

He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12 Page 37

He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12 Read online

Page 37

Ramses put the mouse on his bureau. Seshat sat down and began washing her face.

“Leave it, Mother.” He removed the coat and tossed it onto the bed. Except for the half-healed wounds, his tanned chest and back were unmarked. “I’m as hungry as a pariah dog. Father needs your care more than I. I’m surprised you haven’t been at him already.”

“He was too hungry.” I watched him pull a shirt from the cupboard and slip into it. “He said he’d fallen off his horse when the poor creature stepped into a hole and broke its leg. What happened?”

“He fell, yes. So did the gelding, when it was struck by a bullet.” He finished buttoning his shirt. “Can you wait for the rest of it? No, I suppose not. We were ambushed. The fellow had us pinned down, and with Father injured it seemed advisable to stay where we were until dark. The man was a German spy. He came out of hiding, and we had a little skirmish. He killed himself rather than be taken prisoner. We started back. When we got onto the caravan road I fired off a few shots, which eventually attracted the attention of the Camel Corps. They escorted us to the barracks at Abbasia.”

The narrative had been as crisp and unemotional as a report. I knew he had not told me everything, and I also knew it was all I was going to get out of him.

Ramses tucked his shirt in. “May we go down now?”

Everyone was having a second breakfast, to Fatima ’s delight; she liked nothing better than feeding as many people as she could get hold of. As soon as she saw Ramses she concentrated her efforts on him, and for some time he was unable to converse at all as she stuffed him with eggs and porridge and bread and marmalade.

Emerson was telling Selim and Daoud—who had not gone home—about the ruins in the desert. “A temple,” he declared dogmatically. “Nineteenth Dynasty. I saw a cartouche of Ramses the Second. We’ll spend a few days out there, Selim, after the end of our regular season.”

Oh, yes, of course, I thought. A few peaceful days in the desert with German spies skulking about and the Turks attacking the Canal and the Camel Corps shooting at anything that moved. What had they done with the body of the dead spy? That would be a pretty thing to come upon in the course of excavation.

Finally I put an end to the festivities by insisting that Emerson bathe and rest. Selim said they would return to Atiyah and await Emerson’s orders. “Tomorrow—” he began.

“Tomorrow?” Emerson exclaimed. “I will join you at Giza in two hours or less, Selim. Good Gad, we’ve missed half a morning’s work as it is.”

I took Emerson away. We had a great deal to talk about.

“Two more shirts ruined,” I remarked, cutting away the remains of both garments. “I want Nefret to have a look at your shoulder, Emerson. I am sure Ramses did the best he could, but—”

“No one could have done better. Did he tell you what happened?”

“A synopsis only. He was distressed about something, I could tell.”

Emerson gave me a somewhat longer synopsis. “The fellow was no older than Ramses, if as old. No one could have stopped him in time, and Ramses’s finger was on the trigger when the gun fired.”

“No wonder he was upset.”

“Upset? You have a gift for understatement, my dear. It was a ghastly sight, and so damnably unnecessary! I hope the bastards who fill the heads of these boys with empty platitudes and then send them out to die burn in the fires of hell for all eternity.”

“Amen. But, Emerson—”

A tap on the door interrupted me. “That must be Nefret,” I said.

“May as well let her in,” Emerson muttered. “She’s as bull–as determined as you.”

Nefret’s examination was brief. “I am glad to see Ramses paid close attention to my lecture. It will be tender for a few days, Professor; I suppose there is no point in my telling you to favor that arm. I will just strap it properly.”

“No, you will not,” said Emerson. “I want to bathe, so take yourself off, young lady. Why are you still wearing your dressing gown? Put on proper clothing, we will leave for the dig as soon as I am ready.”

I encouraged her departure, for I still had a good many questions to put to Emerson. To some of them he could only offer educated guesses, but it was evident that the ambush had been arranged by a man high in military or official circles, and that he was in communication with the enemy by wireless or other means.

“We knew that,” I said, pacing up and down the bath chamber while Emerson splashed in the tub. “And we are no closer to learning his identity. You say a number of officers overheard your conversation?”

“Yes. Maxwell also knew of our intentions. He may have let something slip to a member of his staff.”

“Curse it.”

“Quite,” Emerson agreed. “Too damned many people know too damned much. I don’t suppose you have heard from Russell?”

“Er…”

Emerson heaved himself up and stood like the Colossus of Rhodes after a rainstorm, water streaming down his bronzed and muscular frame. “Out with it, Peabody . I knew you were guilty of something, you have a certain look.”

“I had every intention of telling you all about it, Emerson.”

“Ha,” said Emerson. “Hand me that towel, and start talking.”

Having determined—as I had said—to conceal nothing from my heroic spouse, I told him the whole story, from start to finish. I rather pride myself on my narrative style. Emerson certainly found it absorbing. He listened without interrupting, possibly because he was too stupefied to compose a coherent remark. The only sign of emotion he exhibited was to turn crimson in the face when I described Sethos’s advances.

“He kissed you, did he?”

“That was all, Emerson.”

“More than once?”

“Er—yes.”

“How often?”

“That would depend on how one defines and delimits—”

“And held you in his arms?”

“Quite respectfully, Emerson. Er—on the whole.”

“It is impossible,” said Emerson, “to hold respectfully in one’s arms a woman married to another man.”

I began to think I ought to have heeded Abdullah’s advice.

“Forget that, Emerson,” I said. “It is over and done with. The most important thing is that Sethos has got away. I am afraid—I am almost certain—he knows about Ramses.”

“You think so?”

“I told you what he said.”

“Hmmm, yes.”

I had insisted upon helping him to dress, since it is difficult to pull on trousers and boots with only one fully functional arm. Frowning in a manner that suggested profound introspection rather than temper, he slipped his arm into the shirt I held for him, and made no objection when I began buttoning it.

“What are we going to do?” I demanded.

“About Sethos? Leave it to Russell. Ouch,” he added.

“I beg your pardon, my dear. Stand up, please.”

He stood staring into space with all the animation of a mummy while I finished tidying him up and wound a few strips of bandage across his shoulder and chest to support his arm. Then I said, “Emerson.”

“Hmph? Yes, my dear, what is it?”

“I would like you to hold me, if it won’t inconvenience you too much.”

Emerson can do more with one arm than most men can do with two. Yielding to his hard embrace, returning his kisses, I hoped I had convinced him that no man would ever take his place in my heart.

There were three statues in the serdab. The most charming depicted the Prince and his wife in a pose that had become familiar to me from many examples, and one which never failed to please me. They stood close to one another, with her arm round his waist, and the two figures were of almost equal height; the lady was a few inches shorter, just as she may have been in life. She wore a simple straight shift and he a kilt pleated on one side. Their faces had the ineffable calm with which these believers faced eternity. Some of the original paint remained: the white of

their garments, the black of the wigs, the yellowish skin of the lady and the darker brown of her husband’s. Women were always depicted as lighter in color than men, presumably because they spent less time under the sun’s rays than their spouses.

There was another, smaller, statue of the Prince, and one of a youth who was identified as his son. By the middle of the afternoon we had them out; not even the largest was anything like the weight of the royal statue.

“Get them back to the house, Selim,” Emerson ordered, passing his sleeve over his perspiring brow.

Nefret announced her intention of going to the hospital for a few hours and started toward Mena House, where we had left the horses. As soon as she was out of earshot, Ramses said, “I’m off too.”

“Where?” I demanded, trying to catch hold of him.

“I have a few errands. Excuse me, Mother, I must hurry. I will be home in time for dinner.”

“Put on your hat!” I called after him. He turned and waved and went on. Without his hat.

When Emerson and I reached Mena House we found Asfur, whom Ramses had ridden that day, still in the stable. “He’s taken the train,” I said out of the corner of my mouth. “That means—”

“I know what it means. Mount Asfur , Peabody , and I’ll lead the other creature. And do keep quiet!”

I realized I ought to have anticipated that Ramses would have to communicate with one or another, or all, of several people. That did not mean I liked it. My nerves had not fully recovered from the anxiety of the previous day and night. Emerson and I jogged on side by side, each occupied with his or her own thoughts; I could tell by his expression that his were no more pleasant than mine. Superstition is not one of my weaknesses, but I was beginning to feel that we labored under a horrible curse of failure. Every thread we had come upon broke when we tried to follow it. Two of the most hopeful had failed within the past twenty-four hours: my unmasking of Sethos, and Emerson’s capture of the German spy. Now Sethos was on the loose with his deadly knowledge, and the failure of the ambush would soon be known to the man who had ordered it. What would he do next? What could we do next?

Emerson and I discussed the matter as we drank our tea and sorted through the post. I had not done so the day before, so there was quite an accumulation of letters and messages.

“Nothing from Mr. Russell,” I reported. “He’d have found some means of informing us if he had caught up with Sethos.”

Emerson said, “Hmph,” and took the envelopes I handed him.

“There is one for you from Walter.”

“So I see.” Emerson ripped the envelope to shreds. “They have had another communication from David,” he reported, scanning the missive.

“I wish we could say the same. Do you think Ramses will speak with him this afternoon?”

“I don’t know.” Emerson plucked irritably at the strips of bandage enclosing his arm. “Curse it, how can I open an envelope with one hand?”

“I will open them for you, my dear.”

“No, you will not. You always read them first.” Emerson tore at another envelope. “Well, well, fancy that. A courteous note from Major Hamilton congratulating me on another narrow escape, as he puts it, and reminding me that he made me the loan of a Webley. I wonder what I did with it.”

“Does he mention his niece?”

“No, why should he? What does Evelyn say?”

He had recognized her neat, delicate handwriting. I knew what he wanted most to hear, so I read the passages that reported little Sennia’s good health and remarkable evidences of intelligence. “She keeps us all merry and in good spirits. Lately she has taken to dressing Horus up in her dolly’s clothing and wheeling him about in a carriage; you would laugh to see those bristling whiskers and snarling jaws framed by a ruffled bonnet. He hates every minute of it but is putty in her little hands. Thank God her youth makes it possible for us to keep from her the horrible things that are happening in the world. Every night she kisses your photographs; they are getting quite worn away, especially Ramses’s. Even Emerson would be touched, I think, to see her kneeling beside her little cot asking God to watch over you all. That is also the heartfelt prayer of your loving sister.”

“And here,” I said, holding out a grubby, much folded bit of paper, “is an enclosure for you from Sennia.”

Emerson’s eyes were shining suspiciously. After he had read the few printed words that staggered down the page, he folded it again and tucked it carefully into his breast pocket.

There was no message for Ramses that day or the day after, or the day after that. Days stretched into weeks. Ramses went almost every day to Cairo . I never had to ask whether he had found the message he was waiting for. Govern his countenance as he might, his stretched nerves showed in the almost imperceptible marks round his eyes and mouth, and in his increasingly acerbic responses to perfectly civil questions. Some of his visits were to Wardani’s lieutenants; like the rest of us, they were becoming restive, and Ramses admitted he was having some difficulty keeping them reined in.

Rumors about the military situation added another dimension of discomfort. In my opinion it would have been wiser for the authorities to publish the facts; they might have been less alarming than the stories that were put about. There were one hundred thousand Turkish troops massed near Beersheba . There were two hundred thousand Turkish troops heading for the border. Turkish forces had already crossed the border and were marching toward the Canal, gathering recruits from among the Bedouin. Jemal Pasha, in command of the Turks, had boasted, “I will not return until I have entered Cairo ”; his chief of staff, von Kressenstein, had an entire brigade of German troops with him. Turkish agents had infiltrated the ranks of the Egyptian artillery; when the attack occurred they would turn their weapons on the British.

Some of the stories were true, some were not. The result was to throw Cairo into a state of panic. A great number of people booked passage on departing steamers. The louder patriots discussed strategy in their comfortable clubs, and entered into a perfect orgy of spy hunting. The only useful result of that was the disappearance of Mrs. Fortescue. It was assumed by her acquaintances that she had got cold feet and sailed for home; we were among the few who knew that she had been taken into custody. That gave me another moment of hope, but like all our other leads, this one faded out. She insisted even under interrogation that she did not know the name or identity of the man to whom she had reported.

“She is probably telling the truth,” said Emerson, from whom I heard this bit of classified information. “There are a number of ways of passing on and receiving instructions. I understand that chap we saw at the Savoy —one of Clayton’s lot—what’s his name?—is claiming the credit for unmasking her.”

“Herbert,” Ramses supplied, with a very slight curl of his lip. “He’s also unearthing conspiracies. According to him, he doesn’t even have to go looking for them; the malcontents come to him, burning to betray one another for money.”

“One of them hasn’t,” said Emerson. “Damnation! The insufferable complacency of men like Herbert will cost us dearly one day.”

I also learned from Emerson that Russell agreed with his and Ramses’s deductions about the route the gunrunners had followed. The Camel Corps section of the Coastguards had been alerted, and since their pitiful pay was augmented by rewards for each arrest, one might suppose they were hard at it. However, as Russell admitted, the corruption of a single officer would make it possible for the loads to be landed on the Egyptian coast and carried by camel to some place of concealment near the city, where the Turk eventually picked them up. Thus far Russell had been unable to track them.

It was during the penultimate week of January that Ramses returned one afternoon from Cairo with the news we had so anxiously awaited. One look at him told me all I needed to know. I ran to meet him and threw my arms round him.

Eyebrows rising, he said, “Thank you, Mother, but I haven’t come back from the dead, only from Cairo . Yes, Fatima , fresh te

a would be very nice.”

I waited, twitching with impatience, until after she had brought the tea and another plate of sandwiches. “Talk quickly,” I ordered. “Nefret has gone to the hospital, but she will soon be back.”

“She didn’t go directly to the hospital.” Ramses inspected the sandwiches.

“You followed her?” It was a foolish question; obviously he had. I went on, “Where did she go?”

“To the Continental. I presume she was meeting someone, but I couldn’t go into the hotel.”

“No,” Emerson said, giving his son a hard look. “Has she given you any cause to believe she was doing anything she ought not?”

“Good God, Father, of course she has! Over and over! She—” He broke off; his preternaturally acute hearing must have given him warning of someone’s approach, for he lowered his voice and spoke quickly. “I need to attend that confounded costume ball tomorrow night.”

“What confounded costume ball?” Emerson demanded.

“I told you about it several weeks ago, Emerson,” I reminded him. “You didn’t say you would not go, so I—”

“Procured some embarrassing, inappropriate rig for me? Curse it, Peabody —”

“You needn’t come if you’d rather not, Father,” Ramses said somewhat impatiently.

“We’ll come, of course,” Emerson said. “If you need us. What do you want us to do?”

“Cover my absence while I trot off to collect a few more jolly little guns. I got the message this afternoon.” The parlor door opened, and he stood up, smiling. “Ah, Nefret. How many arms and legs did you cut off today? Hullo, Anna, still playing angel of mercy?”

Chapter 12

Over the years we had become accustomed to take Friday as our day of rest, in order to accommodate our Moslem workmen. The Sabbath was therefore another workday for us, and Emerson, who had no sympathy with religious observances of any kind, refused even to attend church services. He had often informed me that I was welcome to do so if I chose—knowing full well that if I had chosen I would never have felt need of his permission—but it was too much of a nuisance to get dressed and drive into Cairo for what is, after all, only empty ceremony unless one is in the proper state of spiritual devotion. I feel I can put myself into the proper state wherever I happen to be, so I rise early on Sunday morning and read a few chapters from the Good Book and say a few little prayers. I say them aloud, in the hope that Emerson may be edified by my example. Thus far he has displayed no evidence of edification; in fact, he is sometimes moved to make critical remarks.

Mystery Stories

Mystery Stories A River in the Sky

A River in the Sky He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12

He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12 Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6

Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6 Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3

Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3 Night Train to Memphis vbm-5

Night Train to Memphis vbm-5 Borrower of the Night vbm-1

Borrower of the Night vbm-1 The Golden One

The Golden One Trojan Gold vbm-4

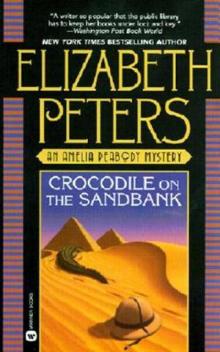

Trojan Gold vbm-4 Crocodile On The Sandbank

Crocodile On The Sandbank