- Home

- Elizabeth Peters

The Golden One Page 4

The Golden One Read online

Page 4

“A very expensive pot,” I amended. “I have the pot as well – an exquisitely shaped alabaster container, most probably for cosmetics. Now shall we go back to the hotel where we can examine it in private?”

“Hmmm, yes, certainly.” Emerson watched me rewrap the lid. “I beg your pardon, my dear. You were quite right to scold me. What else have you got?”

“Nothing so exciting as the cosmetic jar,” I said, “but I believe they are all from the same tomb – the one Cyrus told us about.”

“So Mohassib didn’t get everything.” Emerson strode along beside me, his hands in his pockets. “How did Aslimi come by these?”

“Not from Sethos.”

“You asked him point-blank, I suppose,” Emerson grumbled. “Aslimi is a congenital liar, Peabody. How do you know he was telling you the truth?”

“He turned pea-green at the very mention of ‘the Master.’ It would have been rather amusing if he had not been in such a state of abject terror; he kept wringing his hands and saying, ‘But he is dead. He is dead, surely. Tell me he is really dead this time, Sitt!’ ”

“Hmmm,” said Emerson.

“Now don’t get any ideas about pretending you are ‘the Master,’ Emerson.”

“I don’t see why I shouldn’t,” said Emerson sulkily. “You are always telling me I cannot disguise myself effectively. It is cursed insulting. So – from whom did Aslimi acquire these objects?”

“He claimed the man was someone he’d never seen before.”

“I trust you extracted a description?”

“Certainly. Tall, heavyset, black beard and mustache.”

“That’s no help. Even if it was true.”

“Aslimi would not lie to me. Emerson, please don’t walk so fast.”

“Ha,” said Emerson. But he slowed his steps and gave me his arm. We had emerged onto the Muski, with its roaring traffic and European shops. “We’ll just have time to tidy up before luncheon,” he added. “Do you suppose the children are back?”

“One never knows. I only hope they haven’t got themselves in trouble.”

“Why should you suppose that?”

“They usually do.”

FROM MANUSCRIPT H

The infamous Red Blind district of Cairo was centered in an area embarrassingly close to the Ezbekieh and the luxury hotels. In the brothels of el-Wasa, Egyptian, Nubian, and Sudanese women plied their trade under conditions of abject squalor. In theory they were under government medical supervision, but the government’s only concern was the control of venereal disease. There had been no place for the women who had suffered beatings or botched abortions or illnesses of other kinds. Even more difficult to control were the brothels in the adjoining area of Wagh el-Birka, which were populated by European women and run by European entrepreneurs. They were foreigners and therefore subject only to the authority of their consuls. Ramses had heard Thomas Russell, the assistant commander of the Cairo police, cursing the restrictions that prevented him from closing down the establishments.

The alleys of el-Wasa were fairly quiet at that early hour. The stench was permanent; even a hard rain only stirred up the garbage of the streets and gathered it in oily pools, where it settled again once the water had evaporated. There were no drains. Ramses glanced at his wife, who walked briskly through the filth, giving it no more attention than was necessary to avoid the worst bits, and not for the first time he wondered how she could bear it. To his eyes she was always radiant, but in this setting she glowed like a fallen star, her golden-red hair gathered into a knot at the back of her head and her brow unclouded.

Initially the clinic had been regarded with suspicion and dislike by the denizens of the Red Blind district, and Nefret and her doctor friend Sophia had deemed it advisable not to advertise its presence. Now it was under the protection of the Cairo police. Russell sent patrols around frequently and came down hard on anyone who tried to make trouble. Emerson had also come down hard on a few offenders who had not known that the person in charge was the daughter of the famed Father of Curses. They knew now. Nefret had found another, unexpected supporter in Ibrahim el-Gharbi, the Nubian transvestite who controlled the brothels of el-Wasa, so the expanded building now proclaimed its mission in polished bronze letters over the door, and the area around it was regularly cleaned of trash and dead animals.

“I’ll not come in this time,” Ramses said, when they reached the house.

Nefret gave him a provocative smile. “You don’t like trailing round after me and Sophia, do you?”

He didn’t, especially; he felt useless and ineffective, and only too often, wrung with pity for misery he was helpless to relieve. This time he had a valid excuse.

“I saw someone I want to talk with,” he explained. “I’ll join you in a bit.”

“All right.” She didn’t ask who; her mind was already inside the building, anticipating the duties that awaited her.

He went back along the lane, kicking a dead rat out of his path and trying to avoid the deeper pools of slime. The man he had seen was sitting on a bench outside one of the more pretentious cribs. He was asleep, his head fallen back and his mouth open. The flies crawling across his face did not disturb his slumber; he was used to them. Ramses nudged him and he looked up, blinking.

“Salaam aleikhum, Brother of Demons. So you are back, and it is true what they say – that the Brother of Demons appears out of thin air, without warning.”

Ramses didn’t point out that Musa had been sound asleep when he approached; his reputation for being on intimate terms with demons stood him in good stead with the more superstitious Egyptians. “You have come down in the world since I last saw you, Musa. Did el-Gharbi dismiss you?”

“Have you not heard?” The man’s dull eyes brightened a little. It was a matter of pride to be the first to impart information, bad or good, and he would expect to be rewarded. He looked as if he could use money. As a favorite of el-Gharbi he had been sleek and plump and elegantly dressed. The rags he wore now barely covered his slender limbs.

“I will tell you,” he went on. “Sit down, sit down.”

He shifted over to make room for Ramses. The latter declined with thanks. Flies were not the only insects infesting Musa and his clothes.

“We knew the cursed British were raiding the houses and putting the women into prison,” Musa began. “They set up a camp at Hilmiya. But my master only laughed. He had too many friends in high places, he said. No one could touch him. And no one did – until one night there came two men sent by the mudir of the police himself, and they took my master away, still in his beautiful white garments. They say that when Harvey Pasha saw him, he was very angry and called him rude names.”

“I’m not surprised,” Ramses murmured. Harvey Pasha, commander of the Cairo police, was honest, extremely straitlaced, and rather stupid. He probably hadn’t even been aware of el-Gharbi’s existence until someone – Russell? – pointed out to him that he had missed the biggest catch of all. Ramses could only imagine the look on Harvey ’s face when el-Gharbi waddled in, draped in women’s robes and glittering with jewels.

Musa captured a flea and cracked it expertly between his thumbnails. “He is now in Hilmiya, my poor master, and I, his poor servant, have come to this. The world is a hard place, Brother of Demons.”

Even harder for the women whose only crime had been to do the bidding of their pimps and their clients – many of them British and Empire soldiers. Ramses couldn’t honestly say he was sorry for el-Gharbi, but he was unhappily aware that the situation had probably worsened since the procurer had been arrested. El-Gharbi had ruled the Red Blind district with an iron hand and his women had been reasonably well treated; he had undoubtedly been replaced by a number of smaller businessmen whose methods were less humane. The filthy trade could never be completely repressed.

“My master wishes to talk with you,” Musa said. “Do you have a cigarette?”

So Musa had been on the lookout for him, and had put himself del

iberately in Ramses’s way. Somewhat abstractedly Ramses offered the tin. Musa took it, extracted a cigarette, and calmly tucked the tin away in the folds of his robe.

“How am I supposed to manage that?” Ramses demanded.

“Surely you have only to ask Harvey Pasha.”

“I have no influence with Harvey Pasha, and if I did, I wouldn’t be inclined to spend it on favors for el-Gharbi. Does he want to ask me to arrange his release?”

“I do not know. Have you another cigarette?”

“You took all I had,” Ramses said.

“Ah. Would you like one?” He extracted the tin and offered it.

“Thank you, no. Keep them,” he added.

The irony was wasted on Musa, who thanked him effusively, and held out a suggestive hand. “What shall I tell my master?”

Ramses dropped a few coins into the outstretched palm, and cut short Musa’s pleas for more. “That I can’t do anything for him. Let el-Gharbi sweat it out in the camp for a few months. He’s too fat anyhow. And if I know him, he has his circle of supporters and servants even in Hilmiya, and methods of getting whatever he wants. How did he communicate with you?”

“There are ways,” Musa murmured.

“I’m sure there are. Well, give him my…” He tried to think of the right word. The only ones that came to mind were too friendly or too courteous. On the other hand, the procurer had been a useful source of information in the past, and might be again. “Tell him you saw me and that I asked after him.”

He added a few more coins and went back to the hospital. Dr. Sophia greeted him with her usual smiling reserve. Ramses admired her enormously, but never felt completely at ease with her, though he realized there was probably nothing personal in her lack of warmth. She had to deal every day with the ugly results of male exploitation of women. It would not be surprising if she had a jaundiced view of all men.

He met the new surgeon, a stocky, gray-haired American woman, who measured him with cool brown eyes before offering a handclasp as hard as that of most men. Ramses had heard Nefret congratulating herself on finding Dr. Ferguson. There weren’t many women being trained in surgery. On the other hand, there weren’t many positions open to women surgeons. Ferguson had worked in the slums of Boston, Massachusetts, and according to Nefret she had expressed herself as more concerned with saving abused women than men who were fool enough to go out and get themselves shot. She and Sophia ought to get along.

As Ramses had rather expected, Nefret decided to spend the rest of the day at the hospital. She was in her element, with two women who shared her skills and her beliefs, and Ramses felt a faint, unreasonable stir of jealousy. He kissed her good-bye and saw her eyes widen with surprise and pleasure; as a rule he didn’t express affection in public. It had been a demonstration of possessiveness, he supposed.

Walking back toward the hotel, head bent and hands in his pockets, he examined his feelings and despised himself for selfishness. At least he hadn’t insisted she wait for him to escort her back to the hotel. She’d have resented that. No one in el-Wasa would have dared lay a hand on her, but it made him sick to think of her walking alone through those noisome alleys, at a time of day when the houses would be opening for business and the women would be screaming obscene invitations at the men who leered at them through the open windows.

His parents were already at the hotel, and when he saw what his mother had found that morning, he forgot his grievances for a while. The little ointment jar was in almost perfect condition, and he was inclined to agree with her that the scraps of jewelry – beads, half of a gold-hinged bracelet, and an exquisitely inlaid uraeus serpent – had come from the same Eighteenth Dynasty tomb Cyrus had told them about.

“Aslimi claimed the seller was unknown to him?” he asked. “That’s rather odd. He has his usual sources and would surely be suspicious of strangers.”

“Aslimi would not dare lie to me,” his mother declared. She gave her husband a challenging glance. Emerson did not venture to contradict her. He had something else on his mind.

“Er – I trust you and Nefret have given up the idea of visiting the coffeeshops?”

“I wasn’t keen on the idea in the first place,” Ramses said.

“Well. No need for such an expedition now; your mother questioned the dealers and none of them had heard of the Master’s return. Be ready to take the train tomorrow, eh?”

“That depends on Nefret. She may not want to leave so soon.”

“Oh. Yes, quite. Is she still at the hospital? You arranged to fetch her home, I presume.”

“No, sir, I didn’t.”

Emerson’s brows drew together, but before he could comment his wife said, “Is there something unusual about that ointment jar, Ramses?”

He had been holding it, turning it in his hands, running his fingers along the curved sides. He gave her a smile that acknowledged both her tactful intervention and her perceptiveness. “There’s a rough section, here on the shoulder. The rest of it is as smooth as satin.”

“Let me see.” Emerson took it from him and carried it to the window, where the light was stronger. “By Gad, you’re right,” he said, in obvious chagrin. “Don’t know how I could have missed it. Something has been rubbed off. A name? An inscription?”

“The space is about the right size for a cartouche,” Ramses said.

“Can you see anything?”

“A few vague scratches.” Direct sunlight shimmered in the depths of the pale translucent stone. “It looks as if someone has carefully removed the owner’s name.”

“Not the thief, surely,” his mother said, squinting at the pot. “An inscribed piece would bring a higher price.”

“True.” Emerson rubbed his chin. “Well, we’ve seen such things before. An enemy, wishing to condemn the owner to the final death that befalls the nameless, or an ancient thief, who intended to replace the name with his own and never got round to it.”

Having settled the matter to his satisfaction, he was free to worry about Nefret. He didn’t criticize Ramses aloud, but he kept looking at his watch and muttering. Fortunately she returned before Emerson got too worked up.

“I hope I’m not late for tea,” she said breezily. “Have I time to change?”

“You had better,” Ramses said, inspecting her. Not even Nefret could pass through the streets of el-Wasa without carrying away some of its atmosphere. “How did it go?”

“Just fine. I’ll tell you about it later.”

She rather monopolized the conversation at tea, which they took on the terrace. Even Sennia found it difficult to get a word in.

I could tell Ramses was perturbed about something and I suspected it had to do with the hospital; yet nothing Nefret said indicated that she was unhappy about the arrangements. Unlike my son, Nefret does not conceal her feelings. Her eyes shone and her cheeks were prettily flushed as she talked, and when Sennia said pensively, “I would like to come and help you take care of the sick ladies, Aunt Nefret,” she laughed and patted the child’s cheek.

“Someday, Little Bird. When you are older.”

“Tomorrow I will be older,” Sennia pointed out.

“Not old enough,” Emerson said, trying to conceal his consternation. “Anyhow, we must be on our way to Luxor shortly. Nefret, when can you be ready?”

“Not tomorrow, Father. Perhaps the following day.”

She went on to explain that she had arranged to dine with Dr. Sophia and the new surgeon, Miss Ferguson. A flicker of emotion crossed my son’s enigmatic countenance when she indicated she would like him to be present. He nodded in mute acquiescence, but Emerson firmly declined the invitation. The idea of spending the evening with three such determined ladies, discussing loathsome diseases and gruesome injuries, did not greatly appeal to him.

So we had an early dinner with Sennia, which pleased her a great deal. It did not please Horus, who had to be shut in Sennia’s room, where (as I was later informed by the sufragi) he howled like a jackal the e

ntire time. As we left the dining saloon, we were hailed by an individual I recognized as the apple-cheeked gentleman who had been one of our fellow passengers. His wife was even more resplendent in jewels and satin. Sennia would have stopped, but Emerson hustled her on past, and the gentleman, encumbered by the large menu and even larger napkin, was not quick enough to intercept us.

“Curse it,” said my spouse, “who are those people? No, don’t tell me, I don’t want to know.”

After returning Sennia to Basima, who had taken refuge from Horus in the servants’ dining hall, I settled down with a nice book – but I kept an eye on Emerson. I can always tell when he is up to something. Sure enough, after pretending to read for fifteen minutes, he got up and declared his intention of taking a little stroll.

“Don’t disturb yourself, my dear,” he said. “You look very comfortable.”

And out he went, without giving me time to reply.

I waited a quarter of an hour before closing my book. A further delay ensued when I attempted to get out of my evening frock, which buttoned down the back; however, I was not in a hurry. I knew where Emerson was going, and I fancied it would take him a while to get there. After squirming out of the garment I assumed my working costume of trousers, boots, and amply pocketed coat, took up my parasol, left the hotel, and hailed a cab.

I assumed Emerson would have gone on foot and kept a sharp eye out for that unmistakable form, but there was no sign of him. When we reached the Khan el Khalili I told the driver to wait and plunged into the narrow lanes of the suk.

Aslimi was not happy to see me. He informed me that he was about to close. I informed him that I had no objection, entered the shop, and took a chair.

Aslimi waddled about, closing and locking the shutters, before he seated himself in a huge armchair of Empire style, its arms and legs ornately gilded, and stared hopelessly at me. “I told you all I know, Sitt. What do you want now?”

“Are you expecting someone, Aslimi?”

“No, Sitt, I swear.”

Mystery Stories

Mystery Stories A River in the Sky

A River in the Sky He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12

He Shall Thunder in the Sky taps-12 Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6

Laughter of Dead Kings vbm-6 Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3

Silhouette in Scarlet vbm-3 Night Train to Memphis vbm-5

Night Train to Memphis vbm-5 Borrower of the Night vbm-1

Borrower of the Night vbm-1 The Golden One

The Golden One Trojan Gold vbm-4

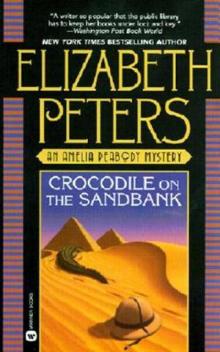

Trojan Gold vbm-4 Crocodile On The Sandbank

Crocodile On The Sandbank